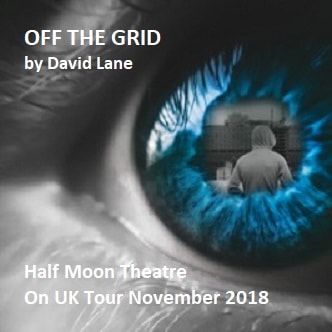

In November 2018 my new play for teenage audiences Off The Grid goes on tour with Half Moon Theatre. In an interview with the company, I was asked to think about what motivated the play and how and why I’ve gone about developing it.

Tell us a little about Off the Grid. What’s the show about?

It’s about two abandoned children: a brother who at thirteen makes an impossible promise to his three year-old sister. He does this for the most genuine, humane and compassionate reasons, but doesn’t know it’s impossible when he makes it.

By the time he realises, he knows that in breaking it he’ll destroy the only thing that has made their joint experience of a cruel world bearable. But without surrendering that thing, he can’t fulfil his own needs as a human being. Can he sacrifice his needs to maintain someone else’s happiness, and can he keep the biggest promise he’s ever made to the one person he’s vowed to protect?

On a larger scale, the play is exploring how we use fictions and play to protect our children from the realities of the world. It questions how much is too much, and what happens when you use storytelling to survive in an inhumane world, but it ends up isolating you from facing up to reality.

What was the inspiration for the story?

I became a Dad. I was spending hours and hours making up stories with my daughter when she was two and a half, and that story world is in good health now: she’s five and a half but bath time is still full of hundreds of interconnected characters and backstories and sub-plots!

We live behind a cemetery and it’s very beautiful – we go walking in there all the time. She was an early reader, and at a very early age after reading the gravestones one day and asking us what they were for, suddenly grasped the concept of death and was utterly inconsolable.

At least, she was inconsolable until we told her all bodies go back into the ground and help the flowers grow, and she said as long as the flower was purple that would be fine and then she seemed fine with her own mortality after all.

I’ve always been gripped by the power of story – particularly through theatre – to transform our perception of reality, but having a child ended up putting that question front and centre in my daily life.

Which questions should be answered with a full truth? What are the ones where the answers require subtleties of language to circumvent or dampen the severity of the truth? How much truth is too much?

Why do the issues covered in Off the Grid particularly resonate with you?

I wanted to write a sibling story, but through that to explore the role of a parent. What might happen if you shouldered a young person who had passion and creativity and hope with the responsibilities of being a parent – and how does that conflict with the huge self-discoveries that occur when you change so much between the ages of 13 and 20?

What happens when the values that you’ve invested into creating a whole fictional world, for the benefit of somebody else’s protection, are no longer compatible with how you see yourself?

I’ve always been fascinated by writing for teenagers for that reason of extremity and transformation – it chimes with something the playwright Fin Kennedy said once about adolescence being a continuing period of ‘coming out’, as you rediscover your place in the world over and over again and renegotiate your position.

I was therefore interested in the passion of possibility and the well of hope that young people have for change, but how so often it’s dulled or curbed by global forces or social media or parents’ disillusioned experiences of the world – those dominant narratives that communicate the dreariness and desperation of the political situation, especially with Brexit and Trump (which occurred mid-writing).

Teenagers are our now and our future, but it’s vital that they’re made to feel it’s possible to change the world. The brother takes this too far, but in such a beautiful and creative way that it’s irresistible to him (and hopefully the audience too), even when his sister and his girlfriend are clearly phasing back into reality.

The political angle of the work that’s connected with me sort of crept up. Once I realised I was writing about a family on the poverty line, I researched more about child poverty, teenager carers and so on, and whilst I learned lots of facts and figures, what I also noticed was that none of these stories seemed as important to the media as shouting about immigration being the end of days.

That’s a generalisation, but along with that shouting comes a lack of compassion, and at the chilling end of lack of compassion is the horrible neglect of children – just look at what’s happening now in the US over border detentions – but it can be more insidious than that too: by that I mean neglect of not just their safety but neglect of their hopes and trust in the world being a place of positive potential – that’s just as terrifying and disturbing a prospect. Connor doesn’t know this intellectually, but he feels it in his heart – at the end of the day he looks out of the window and just wants something better for his sister.

The play takes place between 2016 and 2023. What does this the seven-year span reveal about the characters?

It reveals how their values change, as they continue to discover more about themselves in conversation with the world around them. It reveals a burgeoning understanding of compassion being the greatest political tool that they can wield in an unjust world.

It also reveals what both of them choose to do when, like many of us, they have made incredibly bold life choices with a huge amount of self-belief and confidence and desire to follow-through, then at some point have those choices challenges as misguided, erroneous and ill-judged.

I wanted to drag Connor – the brother – through a wrenching period of self-doubt and horrible compromise, where the person for whom he cares most in the world suddenly becomes an obstacle to his own deeper needs.

That felt like a darker side of becoming a parent that a lot of people don’t talk about – and I should add that whilst it’s a dramatic amplification of anything I’ve ever felt, I know it’s not an unreasonable fiction to suggest that this can sometimes be the case for new parents.

The play is written in a mixture of prose and verse. Why is this and what does each writing style bring to the piece?

I first began exploring the layout of monologue and dialogue more like verse years and years ago, but it came to the fore when I was writing Free for Half Moon back in 2013-14, and was searching for a notation of theatrical language that could communicate more to the performer about the play’s subject matter – parkour and free-running – and that could score not just action but rhythm, movement, tempo, physicality, moving image and music.

Quite a few people say my writing can be listened to as much as watched, which I take as a compliment! But I’m interested in how the rhythm of free verse can add to our journey through a story, and how one performer’s voice in the space can utterly transport us through image, metaphor and poetry.

In Off The Grid however, I needed to ground the piece linguistically by way of contrast to Connor’s wild and imaginative fictions – the prose sections offer a much more grounded experience of the story world, as witnessed by onlookers rather than Connor.

As an audience, that means quite a few times we get to understand the same moment in the plot from very different perspectives: and to me that’s a stylistic choice that supports the blurred lines between fiction, reality and truth that the piece is exploring.

I’m always curious to see how form, style, structure and metaphor can coalesce in a play’s dramaturgy to fundamentally support its themes and narrative. Writing is so much more than just plotting the story, and in theatre I think we’re able to really push those boundaries of what it means to communicate a human experience.

What process do you go through when writing a new play?

Usually there’s a curiosity or question that leads to a huge amount of research – interviews, reading, taking photographs, embedding myself in the subject matter, then sifting back through it and distilling down to the essence of the story – but with this play, because of the amount of myth-making and story-creating involved, I resisted it.

I wrote up the idea quite quickly and tried to write more instinctively: which was aided by Half Moon’s incredible Careers in Theatre programme where playwrights are able to hear very early work – just a page or two of exploratory and very open writing – responded to by over 100 school children of the target age range in a matter of days, via music, image, design, lighting and performance. The muscularity that brings to the formation of an idea is tremendous, and it always brings you belief as a writer in what you’re doing.

After that I become very diagrammatic and structure-oriented, looking for the metaphor at the heart of the work and starting to play with story designs and shapes that can allow me to see the whole shape of the play on a single (often very large!) sheet of paper.

Then it’s about using that to create the first drafts, and then onwards via feedback with actors and a director draft by draft to hone, trim, edit, shift and ultimately nudge the work closer and closer towards being rehearsal-room ready. I find first drafts the slowest and hardest part of the process – I much prefer re-writing to originating material.

What can audiences look forward to?

A performer transforming into multiple characters, a stunning soundtrack, a story about hope, compassion and justice, and a joyful celebration of childhood’s freedoms alongside a serious consideration of how reality too often constricts those freedoms.

Describe Off the Grid in three words.

Gripping, provocative and moving.

What inspired your career as a writer? What advice would you give to young people hoping to follow in your footsteps?

The number one thing that inspired me is the same number one piece of advice I give to people wanting to be writers now: permission. Seek out permission from others or from within yourself to be a writer, or the writer, in an environment that supports you to do so.

I first wrote plays for my Scout troop when I was 12, and then the local amateur dramatic company when I was 14 and 15 – just skits and sketches and rip-offs from Black Adder and Monty Python mostly – but that desire (although the product was often flawed!) was lent so much integrity by the support of those around me, that they were essentially giving me permission to give it a go.

If you can seek out or give yourself validation as a writer, a creator of fictions that can translate your unique experience of the world to others, then you’ll naturally gravitate towards more and more environments that can support you – be they environments of learning, professional experience, work experience, mentoring, or just trying things out with your mates in your room.

Finally, what would you like audiences to take with them after seeing the show?

A feeling of hopefulness and a renewed belief in little creative gestures having big impacts.

Off the Grid is on tour from 7 November – 1 December 2018 with Half Moon.

Enjoy this blog? You can get more insights and receive weekly updates on competitions, awards, submission opportunities, jobs, training and workshops by signing up to Lane’s List – every Thursday, 50 weeks a year, to your inbox.