(A daughter meets her father for the first time in 60 years during the 2015 divided family reunions, whilst journalists, North Korean intelligence and many other families look on)

(Image courtesy of the Korea Times: www.koreatimes.co.kr)

In June 2016, director Sita Calvert-Ennals and I carried out a fortnight of R+D with two performers, a composer, a movement director and sound designer – and a large handful of newly-written scenes – as a creative development from our week-long research trip to Seoul in October 2015.

On that trip we interviewed ex-ministers, peace workers, pressure groups, North Korean defectors, artists and the family members themselves who had been connected to the annual divided family reunion programmes between South and North Korea.

I’ll move onto the ‘top ten’ of the title in a short while, but I thought a bit of context would probably be useful for setting the scene for what happened, and what we learned.

The phrase ‘R+D’ has become synonymous with the progress of new work and is widely seen as an opportunity to learn within a protected environment.

It’s there to take risks, go wide and long, hit the extremes of your ideas, do things you’re not sure about, set up a test-bed for collaboration, work both boldly and carefully with material that perhaps requires an unfamiliar treatment – or is unfamiliar simply because it’s not your native culture, history or lived experience.

The latter – culture, history and lived experience – was a huge part of what drove our application to the Arts Council for funding. It was also what steered some of our decisions regarding which artistic disciplines we felt needed to be involved across the fortnight.

To break it down a little further:

Experience

The story we are telling is an extraordinary experience of survival, hope and separation by a father and daughter. Forced apart through no fault of their own, hundreds of thousands of Korean family members ended up either side of the DMZ following the 1950 – 53 Korean War; many of whom are still alive will never, ever meet those relatives or even know of their whereabouts or status.

Every year however, when political relations are stable, roughly 200 of over 100,000 applicants from the South (the applicant numbers and selection process in the North are unknown) will meet their Northern counterparts in a temporary and rigidly-controlled reunion event in the remote Kumgang Mountain resort just inside the Northern border.

It comprises six meetings of two hours each across three days – only two of which are private – and after which they will never see or have contact with one another again.

(Another daughter and father reunite in 2015)

History

This entire event, even when focusing on just two of the potential (fictional) characters involved, is a compression of complex political histories.

Under the Cho’son family, Korea experienced one of the longest ever consistent dynasties at around 900 years. In the next 100 across the 20th century they withstood invasion and attempted colonisation by the Japanese, arbitrary division at the 38th parallel on the basis of a strategic agreement between the USA and Russia (the USA simply feared Stalin’s strength in taking over the entire peninsula so brokered a deal), a resulting civil war between North and South that ended only in a technicality (they are still officially at war) and since then 63 years of separation with an American-styled liberal democracy (of sorts) in the South, and a secretive totalitarian communist regime in the North.

The two characters who meet in our play are just one generation removed from that entire 100 years. They have personally endured 50 years of completely different political histories. It is in their bones and memories.

Culture

A traditionally patriarchal culture with its roots in Confucianism, the multiple social formalities, routines, rituals and deeply-shared (and then deeply-divided) beliefs and philosophies are the ones in which these characters were brought up by their parents and grandparents.

They’re also very different from the two contemporary Koreas in which they now live (‘now’ being the year 2000 when the play is set, and therefore 15 years before we were in Seoul and treated to a particular set of routines and traditions as visitors in a host culture).

(The curious wedding-like set-up for the public reunion meetings)

Knowing all this, authenticity was therefore a word that had been in play constantly since our trip to Seoul.

How could we, as UK theatre-makers, capture and distill all of this in the storytelling?

How would different theatrical languages, forms and structures help us?

Did we avoid melodrama and tragedy or embrace it – and if we embraced it, how did we show what feels almost unwriteable?

What would it mean to have artistic input – and even simply to be sharing our early script – with Koreans who had greater ownership of this situation than we would ever have?

These challenges were pushed further still when we realised that in combination with the political backdrop of the situation and characters as outlined above, there was something deeply raw, tragic, hopeful, contradictory and human about the real scenes of reunion and farewell we observed via the media: what our methods of staging those would be, and how the resulting conversations across the twelve hours of reunion would be presented, became the backbone of our R+D.

We knew those methods would go beyond text and employ sound, heightened movement, original music, contemporary sound design, non-verbal sequences and possibly film. We knew the narrative structure would need to switch somehow between past and present without feeling too rigid.

We knew we wanted to ‘amplify’ certain moments, perhaps from a specific character, to emphasise particular points of view and perspective. And we wanted to work with UK-based Korean artists to explore how that would shape the storytelling.

That’s a mammoth amount of ‘knowns’ to tackle in two weeks. We hadn’t even hit the wide seam of ‘unknowns’ that R+D regularly throws up too.

On top of all this, we also had two ‘sharings’ programmed for the last two days of the ten, which we roughly anticipated would be 30mins of material – and from which (we are hoping) a relationship with a venue producer would emerge.

So: there’s the set-up (and that’s not the half of it – I could go deeper but we’d be here all day). I’ve only lingered on our own context because it’s the sheer scope and weight of the material – and the responsibility of making strong choices within it that can support everybody else in that exploration – that can threaten to veer you away from a more genuine sense of freedom and looseness in the process, even at the times you need it most.

Anyway, the overall purpose of this blog is to share a little of what we learned – specifically about the aim of capturing a sense of cultural authenticity in our theatrical choices for this story, but also about R+D generally.

So here’s the mixed bag of top-ten tips for R+D (I say top ten, but in no particular order).

Hope you enjoy them…

(Images from the R+D studio space)

1. When making work about other cultures, have someone from that other culture in the room with you

It was always our intention to work with British Korean actors for the R+D, but finding a 53 year-old female and 75 year-old male performer in the UK to fulfil those roles became nigh on impossible despite a huge network of contacts in the Korean community.

However our Korean composer Jae-Moon Lee fulfilled this role of cultural dramaturg from many angles on the days he was with us. He encouraged the existing authenticity of our indicative script and characters, but also offered specificity in terms of politics, cultural habits, traditions and observations of Korean family life.

He also emphasised the emotional and intellectual impact of him ‘re-seeing’ a situation he thought he knew well via our material, which again helped to validate that ‘why’ question of UK theatre makers telling this story.

Plus, he was pretty helpful with more basic discoveries, such as our intended incorporation of the North Korean National Anthem in a play that we hope can tour to Seoul, coming up against the illegality of even playing, singing or humming the tune in South Korea. Oops.

2. Get a documenter or video maker who’s nothing to do with your show

Our film-maker Barney Witts created an informative five-minute trailer showing elements of the R+D process.

In the making of this, his presence had an unexpectedly helpful dramaturgical function: requests for voxpop-style interviews with the creative team demanded that we take an objective step back from the material, and consider how to clearly express both process and intention to an outside audience.

His mantra was ‘just keep it really basic, like I don’t know anything about what you’re doing’. This was gold dust when our heads were swirling with pretty much everything – it often brought us back to the heart of the project and reminded us to speak with simplicity about the people, not just the politics and concept.

3. Research will emerge when you need it in the room

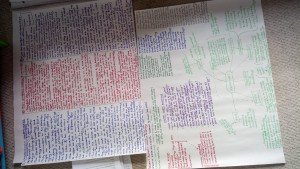

I always felt my strengths in this R+D were definitely in the ‘R’ department – Korean history and politics were coming out of my ears by the time we started. I also created some painstakingly long timelines for characters, the two separate Koreas and the original unified one, in line with the character histories (and their parents’) – and then had them all dutifully printed up and displayed in the room (see image below).

They were of course then at their most useful when translated into practical contexts: but facts are foundations, and often they kept me standing when other things were falling around my ears.

4. If it genuinely feels like you can’t write it, don’t

This is not about ability – but is absolutely about the limitations of dialogue. I got hugely derailed by piling way too much pressure on the writing to carry everything.

Movement director Kate Webster was therefore of huge significance in solving challenges in our storytelling. Her methodology for physical work demonstrated different ways for us to express on stage the first meeting of father and daughter after a 50-year separation. She provided opportunities for us to find lightness, humour and variation of tempo and rhythm in the story overall and gifted the whole creative team a new visual vocabulary with which to tell this story.

5. Assume nothing, question everything

Sita and I have worked together on and off for seven years. This is our third project together, but it’s our first R+D of this nature. Our working relationship is incredibly honest and strong, and that’s in part what forged our artistic partnership in the first place: other than liking one another’s work, there was an early recognition of our ability to say ‘I fucked that one up – how do I make it better and stronger next time?’

We both made a small handful of assumptions about one another’s expectations of roles in the room, and it had a big impact on how the R+D progressed. When the Scouts say ‘be prepared’, there’s a reason.

6. Protect the nature of your sharing

For various reasons – and recognising this in retrospect – we got too safe too soon in the process.

We wanted the sharing to show the project in its best light and demonstrate its potential as impressively as possible: but too soon, this manifested itself as a desire to show something seamless and fluid that was more like a polished extract than that rough-and-ready-middle-of-the-process-seat-of-your-pants work that perhaps should be the bread and butter of R+D.

This point isn’t about not having sharings – it’s about being bold in setting the limitations of your sharings, to allow the process beforehand to fully flourish.

(Think sideways – three versions of the show: two of which will never be made)

7. Don’t panic: and sometimes fail on purpose

Really, really, really don’t panic. It’s fine. It’s protected time. Sometimes you’re meant to fail, maybe a hundred times, to work out better what to make, even when all your failed choices began as strong choices.

And ‘fail on purpose’?

I suppose what I really mean is that I hadn’t appreciated the value of opening up creative conversation by deliberately going somewhere you absolutely know won’t be the finished product. I’m an inveterate problem-solver, and often expect the writing to bear the brunt of this too, so will resist making choices unless I’ve an inkling that they’re pointing towards the show in some way.

But the image just above of the ‘three shows’ – which I completed post R+D – is an exercise in just that. Two of these show outlines we knew we never wanted to make: but discussing why was the key that unlocked mine and Sita’s clearest joint understanding so far of what we did want.

But again – really, really do not panic, or you retreat to a space of limitation and fear, and R+D should never be a space of limitation and fear. I’m guilty as charged on this one, and my contributions and effectiveness in the room suffered as a result.

8. Human stories endure beyond the political

The most common advice we were given in Korea about telling this story was ‘show the humanity, not the ideology’. At the same time, each of these characters is carrying the ideology of those two polarised halves of their once-united nation.

One of our huge concerns in the R+D was how to get the politics in the room – we knew the personal could carry it, but we wanted to be more direct.

In our sharings, we were reminded: it’s the human experience that connects us. Don’t give history lessons, don’t educate. Be authentic to the emotional experience (which carries the politics within it).

In addition, harking back to the subheading of ‘Experience’ above, we are all part of families. We are all sons or daughters of somebody. Some of us are parents. We can all understand the idea of separation and reunion, and imagine the idea of loss and the need for hope to see a loved one again. That’s now a much stronger element of how we’re conceiving the show than it was pre-R+D.

9. Recognise pressure and confront it

It would be fair to say there was a large amount of potential pressure held within all of the context described above, and from my point of view it was often that pressure that threatened most the desire to keep it ‘R+D’ – to maintain that genuinely risk-taking, exploratory, pressure-free workshop feel.

At the very point when the process, the material, the dramaturgy and you as artists are likely to be vulnerable, you ask an audience to show up and respond. We knew these things. We didn’t confront and manage them all.

(Sita works on an improvisation with David Tse)

10. Evaluate – allow the dust to settle

We’ve had three evaluations of this R+D now, to cover the personal, artistic and pragmatic outcomes (I only realise that now I’m writing it down). That’s been pretty much three full days of work. All have been invaluable and necessary.

R+D can create revelations, realisations, beautiful moments, laughter, tears, depth of understanding and clarity of intent. It can also bruise you, the project, and even your working relationships: but each emerges undoubtedly stronger.

We’re now in a stronger position than ever, personally, artistically and pragmatically. Our shared vision and creative process for the play is clear. Right at the end of the fortnight, and even after the first evaluation, we simply felt a conflicted mixture of achievement and uncertainty.

Now, we feel more excited than we’ve ever been.

The play created from this process – What Remains of Us – is currently part of an ACE application for regional and London production in 2019.